Consider a business that is doing well but has fewer growth opportunities and another business doing poorly in an attractive growing market. Where will the business invest?

Organizations have limited resources, and there is always competition for these resources among different teams, departments, and business units. Organizations with diversified portfolios find it challenging to decide where to invest the funds.

In such scenarios, the GE McKinsey Matrix comes to the rescue.

McKinsey developed the GE McKinsey Matrix in 1970 for General Electric. This matrix is based on the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) Matrix. General Electric has around 150 different business units. At that time, GE was relying on future cash flow projections and market growth to make investment decisions. This was an unreliable methodology.

To group different businesses based on their cash generation ability and future cash requirements, GE developed a 9-box matrix in consultation with McKinsey. This matrix provides a systematic approach for multi-business corporations to prioritize their investments among different business units or products.

GE McKinsey Matrix

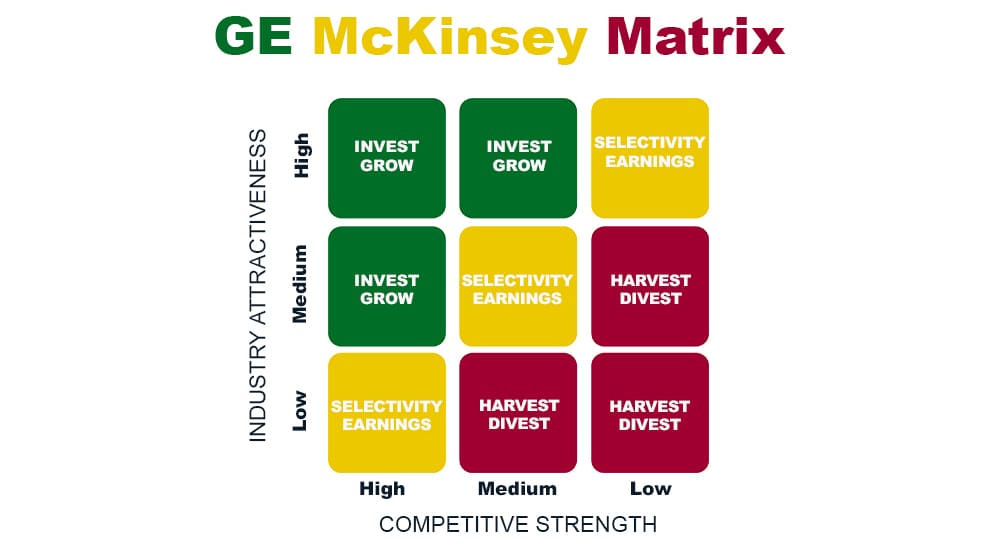

The GE 9-box Matrix plots each product, service, or business unit into nine cells that indicate whether the company should invest, diversify, or do more research.

The GE Matrix has two axes: industry attractiveness (vertical axis) and the competitive strength of the unit (horizontal axis). Each business unit is evaluated on these two parameters.

Industry attractiveness shows the attractiveness of the economic sector in which the product, service, or business unit is located. Competitive strength shows the strength of the organization in that sector.

Industry Attractiveness

Industry attractiveness indicates how hard or easy it is for a business to compete in the market and earn profits. More profit means more attractiveness.

Industry attractiveness is assessed by checking:

- Growth Rate: The business’s current growth rate and how it is expected to perform in the long run.

- Competition: More competitors mean more challenges.

- Entry Barriers: Higher entry barriers are better if the business is established. It will take time for new entrants to become established.

- Profitability: How profitable the product is and if the market has substitutes.

- Industry Structure: Evaluated using the structure-conduct-performance (SCP) model.

- Product Life Cycle Changes: How often products are updated or new products are launched. Newer, more successful products push older products out of the market.

- Changes in Demand: For example, if animal meat is replaced with AI-based meat.

- The Trend of Prices: If prices are volatile and dependent on external factors.

- Seasonality: Checks if there is a demand only in a specific season.

- Availability of Manpower: Checks the workforce availability in the future.

- Market Segmentation: How the market is segmented. For example, most sunglasses are owned by Luxottica and are sold under different names – Ray-Ban, Oakley, Vogue, Armani.

- Macro Environment Factors: Evaluated using a Political, Economic, Social, and Technological (PEST) analysis.

Competitive Strength

Competitive strength indicates how strong a particular product, service, or business unit is against its rivals. How long can the product maintain its competitive advantage?

Competitive strength is assessed by checking:

- Market Share: What is the product’s market share compared to its rivals?

- Average Profitability: How profitable is the segment?

- Size of Product Mix: If Samsung’s Galaxy model is more successful, the company can focus on releasing a series in this product line. This is one product line. Likewise, it can have other product lines. Looking visually at product mixes can help determine the competitive strength.

- Brand’s Strength: How do consumers see the brand, and how is the customer loyalty?

- Product Flexibility: How easily the product can adapt to changes in the market conditions.

These two variables are quantified into three categories: Low, Medium, and High. This creates a 3×3 matrix with 9 scenarios, but three main approaches:

- Invest/Grow

- Selectivity/Earnings

- Harvest/Divest

Fig. GE McKinsey 9-box Matrix showing 3 approaches in 3 colors (Green: Invest/Grow, Yellow: Selectivity/Earnings, Red: Harvest/Divest)

Invest/Grow

Businesses should invest in these segments if a product, service, or business unit falls into this category, as they will give the highest returns. Since these products will operate in a growing market, they will require cash to sustain the market share.

Businesses should ensure there are no constraints for these products to grow. Investments should be provided for doing R&D, advertising, acquiring new products or services, and increasing the production capacity to meet the market demands.

Selectivity/Earnings

Companies should invest in these segments if they have money left over within their business unit and believe they will generate cash in the future. These products have uncertainty and thus are given the least preference.

If there are no dominant players in the industry, the market is enormous; the business should invest if the product falls in this segment.

Harvest/Divest

If a product is in an unattractive industry, has no competitive advantage, and performs poorly, it falls into this category. Businesses that fall into this category should be harvested or divested.

If the products under this segment generate cash, they should be treated like “Cash Cows” in the BCG Matrix. The excess cash should be invested into other segments (harvest). It is worth investing in this segment if the cash generated is always greater than the investments.

If the product is losing, the business should sell the loss-making unit and invest elsewhere (divest).

BCG Matrix Vs GE Mckinsey Matrix

McKinsey’s 9-box matrix is similar to the BCG Matrix, as both help evaluate a company’s portfolio and facilitate investment decisions.

However, they have some differences, for example

- The BCG Matrix focuses on how excess cash from “Cash Cows” segments should be deployed into other segments. In contrast, McKinsey’s 9-box Matrix focuses within the company on how investments need to be prioritized and whether to invest, protect or harvest.

- The BCG Matrix is simpler as it has only four quadrants against GE McKinsey’s 9 quadrants. These 9 quadrants provide a better visual representation of where each business unit stands in the matrix.

- The BCG Matrix has “invest” quadrants (Question Marks and Stars) and “harvest” (to get rid of the quadrant- Dogs) closer. However, in the case of McKinsey’s matrix, they are spaced out as they are standing apart from each other.

- The BCG Matrix assumes that if market share is higher, it is positioned better to compete. This might not be true, it is simplistic, and there could be other factors that should be considered.

- The BCG Matrix classifies businesses as low and high, but there can be medium businesses. For this matrix, the business must fit into one of the buckets, which might not be 100% accurate. In the case of McKinsey’s matrix, it is classified as three degrees: Low, Medium, and High.

GE McKinsey Matrix Example

Let’s take the example of Google. Google’s search engine is the primary Google product, having a 70% market share, and is in the GREEN zone (Invest/Grow). Google’s Chromecast is an innovative product sold at an affordable price. It is in the YELLOW zone (Selective Investment), and Google’s books are in a highly competitive market competing against Amazon and are in the RED zone (Harvest/Divest).

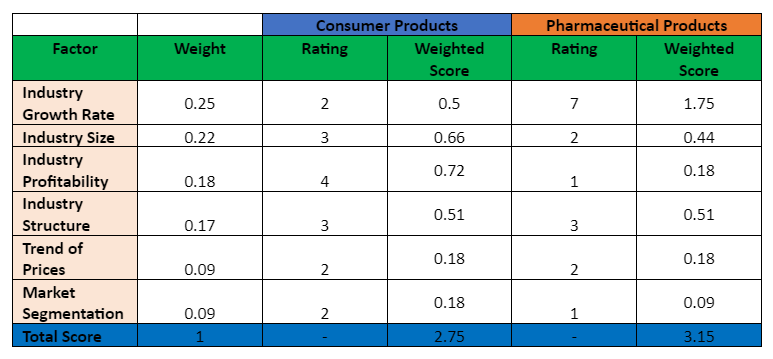

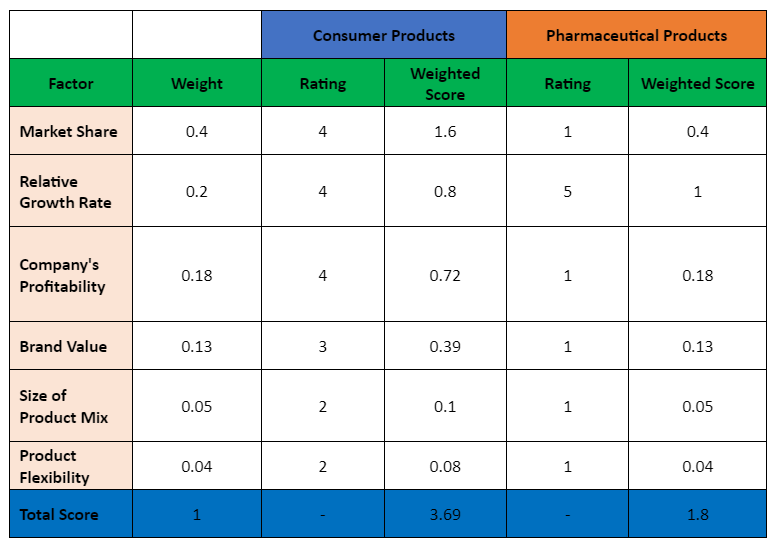

Let’s consider two business units of Johnson & Johnson: Consumer Products (e.g., soaps) and Pharmaceutical Products (e.g., COVID vaccine).

Note: The data below is random and is shown for educational purposes.

Let’s evaluate the Industry Attractiveness of both segments:

Let’s calculate the Competitive Strength of both the segments:

To plot this data on the GE McKinsey 9-box Matrix, here is what it looks like:

From this data, we can infer that Consumer Products (3.69, 2.75) is in YELLOW (Selective Investment) and Pharmaceutical Products (1.8, 3.15) is in GREEN (Invest/Grow).

Limitations of the GE McKinsey Matrix

- It requires a lot of market data, which is challenging for businesses with a diversified portfolio.

- It takes time, effort, and money to plot on the matrix.

- This matrix assumes each segment is independent of others, but sometimes products can be supportive of others.

- If the businesses keep growing, it will look very complex on this matrix.

- Industry attractiveness and competitive strength opinions can vary from one person to another, so it is very subjective rather than objective.

- It is difficult to position a new business unit on this 9-box matrix in a developing industry.

Conclusion

McKinsey’s nine-box matrix is an improvised version of the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) matrix. . This matrix helps companies with diversified portfolios check which business unit a company should invest in, divest, etc.